The broad brushstrokes of history have judged that Dunmore's overwhelming victory over Chief Cornstalk's Indian alliance in the 1774 Battle of Point Pleasant came as a consequence of depredations perpetrated by a "Savage Empire." A careful examination of Jolly's recollections, however, reveals the root cause of the conflict -- a cause bathed in the blood of vengeance.

The Mingo Indian chief known to the white people as "John Logan" sought revenge for the brutal murder of his family by white settlers at Yellow Creek on April 30, 1774. Jolly, a respected jurist, was sixteen years old at the time of the massacre, yet at the age of 75, he recalled the savage incident which led to the Battle of Point Pleasant in striking detail:

In the Spring of the year 1774 a party of Indians encamped on the Northwest of the Ohio, near the mouth of Yellow Creek. A party of whites called Greathouse’s party, lay on the opposite side of the river. The Indians came over to the white party—I think five men, one woman and an infant babe. The whites gave them rum, which three of them drank, and in a short time became very drunk. The other two men and the woman refused. The sober Indians were challenged to shoot at a mark, to which they agreed, and as soon as they emptied their guns, the whites shot them down. The woman attempted to escape by flight, but was also shot down. She lived long enough, however, to beg mercy for her babe, telling them that it was a kin to themselves. They had a man in the cabin, prepared with a tomahawk for the purpose of killing the three drunk Indians, which was immediately done. The party of men, women &c moved off for the interior settlements, and came to Catfish Camp on the evening of the next day, where they tarried until the next day. I very well recollect my mother, feeding and dressing the babe, chirping to the little innocent, and it smiling, however, they took it away, and talked of sending it to its supposed father, Col. Geo. [John] Gibson of Carlisle (Pa.) who was then [and] had been for several years a trader amongst the Indians.

|

| An illustration depicting the Yellow Creek Massacre. Image credit: West Virginia Encyclopedia. |

The remainder of the party, at the mouth of Yellow Creek, finding that their friends on the opposite side of the river was massacred, the[y] attempted to escape by descending the Ohio, and in order to avoid being discovered by the whites, passed on the west side of Wheeling Island, and landed at pipe creek, a small stream that empties into the Ohio a few miles below Graves Creek, where they were overtaken by Cresap with a party of men from Wheeling. They I believe carried him in a litter from Wheeling to Redstone. I saw the party on the return from their victorious campaign.

The Indians had for some time before this event thought themselves intruded upon by the Long Knife, as they called the Virginians at that time, and many of them were for war—however the[y] called a Council, in which Logan acted a conspicuous part. He admitted their ground of complaint, but at the same time reminded them of some aggressions on the part of the Indians, and that by a war, they could but harass and distress the frontier settlements for a short time, that the Long Knife would come like the trees in the woods, and that ultimately, they would be drove from their good land that they now possessed. He therefore strongly recommended peace. To him they all agreed, grounded the hatchet, every thing wore a tranquil appearance, when behold, in came the fugitives from Yellow Creek; Logan’s father, Brother and sister murdered. What is to be done now? Logan has lost three of his nearest and dearest relations, the consequence is that this same Logan, who a few days before was so pacific, raises the hatchet, with a declaration, that he will not ground it, until he has taken ten for one, which I believe he completely fulfilled, by taking thirty scalps and prisoners in the summer of 74. The above has often been told to me by sundry persons who was at the Indian town, at the time of the Council alluded to, and also when the remains of the party came in from Yellow Creek; Thomas Nicholson has told me the above and much more, another person (whose name I cannot recollect) told me that he was at the towns when the Yellow Creek Indians came it, that there was a very Great lamentation by all the Indians of that places, some friendly Indian advised him to leave the Indian Settlement, which he did.

Could any person of common rationality, believe for a moment, that the Indians came to Yellow Creek with hostile intention, or that they had any suspicion of the whites, having any hostile intentions against them? Would five men have crossed the river, three of them in a short time dead drunk, the other two discharging their guns, putting themselves entirely at the mercy of the whites, or would they have brought over a squaw, with an infant papoose, if they had not reposed the utmost confidence in the friendship of the whites? Every person who is acquainted with Indians knows better, and it was the belief of the inhabitants who were capable of reasoning on the subject, that all the depredations committed on the frontiers was by Logan and his party, as a retaliation, for the murder of Logan’s friends at Yellow Creek—I mean all the depredations committed in the year 1774.

Jolly's memory of the Yellow Creek Massacre and the events that followed failed to recall the details of the savage attack on Logan's kin. Others would testify to witnessing a horrific scene in which members of the Greathouse party not only kidnapped a young child and brutally murdered all the natives, but they also mutilated their bodies and disemboweled Logan's pregnant sister. They then scalped and impaled her unborn child on a stake. During the slaughter, one of the attackers cruelly bragged, "Many a deer have I served in this way."

In his grief, Logan called out to the men whom he accused of murdering his family:

"What did you kill my people on Yellow Creek for. The white People killed my kin at Coneestoga a great while ago, & I though[t nothing of that]. But you killed my kin again on Yellow Creek, and took m[y cousin prisoner] then I thought I must kill too; and I have been three time[s to war since but] the Indians is not Angry only myself."

Captain Joh[n Logan] July 21st. Day.

The Yellow Creek Massacre ended all hope Chief Cornstalk had for a peaceful coexistence with the settlers as Logan sought revenge for the brutal slayings. Logan later lamented:

"I appeal to any white man to say if he ever entered Logan's cabin hungry, and he gave him not meat; if he ever came cold and naked and he clothed him not. During the course of the last long and bloody war, Logan remained idle in his cabin, an advocate for peace.... There runs not a drop of my blood in the veins of any living creature. This has called on me for revenge. I have sought it; I have killed many; I have fully glutted my vengeance. For my country, I rejoice in the beams of peace."

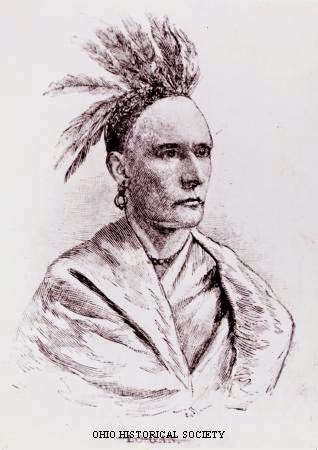

|

| Photographic reproduction of a print depicting John Logan (1725-1780), a chief of the Mingo tribe. Image credit: Ohio History Central. |

In a letter to Colonel William Preston, Major Arthur Campbell urgently pleaded for military intervention. In his letter, Campbell communicated the frequency of Logan's vengeance-fueled assault on the settlers. "So many attacks in so short a time, give the inhabitants very alarming apprehensions," he wrote.

Lord Dunmore answered Campbell's call for reinforcements and exacted his own form of revenge for Logan's personal pursuit of justice, ultimately defeating Cornstalk's Indian warriors at the Battle of Point Pleasant. Although Logan did not participate in the battle itself, he did continue to fight against the Americans in the Revolutionary War. He escaped death until 1780, when ironically, a member of his own family, a nephew, murdered Logan near present-day Detroit, Michigan.

PREVIOUS POSTS:

SELECTED SOURCES:

- "Reminiscences of Judge Henry Jolly," Draper Manuscripts, 6NN22-24, cited in Reuben Gold Thwaites and Louise Phelps Kellogg, Documentary History of Dunmore's War, 1774. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1905, pp. 9-14.

- Colin G. Calloway. The Shawnees and the War for America. New York: Viking, 2007, pp. 51-52.

- Thomas Swift Landon. "Greathouse Party Massacre." e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. August 13, 2012.

- "Logan's Lament (Transcript)." Ohio History Central.

NOTES:

*

According to Thwaites' Documentary History of Dunmore's War, 9n16: “The following was sent to Dr. Draper in 1849, by S. P. Hildreth, who had an interview with Judge Jolly. The latter was sixteen years of age at the time

of these occurrences, and recollected them well. There has been much

controversy over these incidents; for the statements of other contemporaries,

see Sappington, in Jefferson’s Notes on

Virginia (ed. of 1825), pp. 336-339; Tomlinson, in Jacob’s Cresap, pp. 133-137; George Rogers

Clark’s letter, ibid., pp. 154-158; Washington-Crawford Letters, pp. 86, 87;

and N. Y. Colon. Docs., viii, pp.

463-465.—Ed.”

Gordon Belt is an information professional, archives advocate, public historian, and author of The History Press book, John Sevier: Tennessee's First Hero, which examines the life of Tennessee's first governor, John Sevier, through the lens of history and memory. On The Posterity Project, Gordon offers reflections on archives, public history, and memory from his home state of Tennessee.