Showing posts with label memory. Show all posts

Showing posts with label memory. Show all posts

A fond look back, and the road ahead...

It's been more than a decade since I published the first blog post on The Posterity Project way back in 2008. What began as an experiment in social media, sharing links and stories about archives and public history in Tennessee, has grown into an author platform, gaining attention of interested readers from across the state and beyond its borders. Ultimately, the attention we received through our blog led us to our publisher, The History Press, and the publication of our first book, Onward Southern Soldiers: Religion and the Army of Tennessee in the Civil War. Three years later, we published John Sevier: Tennessee's First Hero, a subject that has been a centerpiece of attention here on The Posterity Project for much of this blog's lifespan.

Your interest in our work and our books has provided us with so many opportunities to visit readers, bookstores, heritage and lineage societies, colleges and universities, and historic sites to speak about our books beyond the limited confines of online conversation. We've met a lot of wonderful people who share our passion for history and we're grateful for each opportunity we have to engage with the public. After all, public history is by its very definition a "public" endeavor. I've long believed that social media should be a tool to facilitate public engagement in the real world. As much of our online public discourse has devolved into fits of name-calling, snark, and sarcasm, we need more "social" and less "media," in my opinion.

As we begin work on our third book, we plan to spend more time focused on writing and research. This means stepping away from social media for a while as we read the letters, diaries, journals, legends, and folktales of Tennessee's earliest pioneers and learn more about their interactions with native peoples who arrived at "America's First Frontier" long before them. Posts to The Posterity Project will be far and few between as we explore this topic in greater detail.

Before I sign off, I want to express how grateful we are for the support we've received for our writings on this blog and in our books. It has been a labor of love to share this history with you. We're extraordinarily grateful for your shared interest in the past.

Thank you!

Gordon Belt and Traci Nichols-Belt are a husband and wife team of authors and public historians. Together, they have collaborated on two books. Traci Nichols-Belt is the author of Onward Southern Soldiers: Religion and the Army of Tennessee in the Civil War. Her book explores the significant impact of religion on the Army of Tennessee, C.S.A., on every rank, from generals to chaplains to common soldiers. Gordon Belt is the author of John Sevier: Tennessee’s First Hero, which focuses on the life and legend of Tennessee’s first governor, John Sevier. Both books are published by The History Press, an award-winning publisher of local and regional history titles from coast to coast. Gordon and Traci’s writings focus specifically on stories from their home state of Tennessee.

A visit to Franklin...

Last week, my wife, Traci, had an opportunity to visit the Williamson County Archives and Museum in Franklin, where an audience gathered to hear her speak about her book, Onward Southern Soldiers: Religion and the Army of Tennessee in the Civil War.

Five years after first publishing Traci’s book with The History Press, we remain grateful for the outpouring of support and interest we’ve received for Onward Southern Soldiers. It is a testament to the durability of her scholarship and to the passions readers have for her topic.

Franklin, of course, was once the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. At the Battle of Franklin in November of 1864, the Army of Tennessee lost over 6,000 dead and wounded, including six dead Confederate generals. Altogether, some 10,000 American soldiers became casualties at Franklin. When recollecting the battle years later one man said simply, “It was as if the devil had full possession of the earth.”

Following her talk, Traci took a self-guided tour of Franklin’s Civil War sites, including a brief walk along an area of Franklin once overrun by development. In the years that followed this bloody battle, the march of progress overtook portions of the battlefield. Commercial development consumed the land.

Concern for the loss of tangible remnants of the Battle of Franklin served as one of several factors that motivated Traci to pursue a degree in Public History. This shared concern also led the community of Franklin to preserve portions of the battlefield from the ravages of modernity.

Franklin now serves as a model for battlefield preservation throughout the nation. The citizens of Franklin deserve praise for their diligent work to restore these historic sites. The effort remains a work in progress, but after years of struggle, the results are beginning to pay off.

Times have changed dramatically since our nation’s earliest efforts to preserve Civil War memory. While Civil War monuments and the mythology of the “Lost Cause” continue to influence our narrative and shape public memory, they are no longer the sole source of remembrance.

Following the sesquicentennial anniversary of the war, a healthy debate has emerged from this period of commemoration concerning how best to present a more complete picture of the war and its primary cause—the institution of slavery. Still, society continues to struggle to come to grips with this “peculiar institution” and its legacy.

Battlefield preservation efforts like those taking place in Franklin provide us with an opportunity to learn. By asking difficult questions at the very site where conflict boiled over into battle, we move beyond the mere recitation of battlefield maneuvers and military strategy. We gain an opportunity to engage the public in a conversation about our shared Civil War memory by exploring the painful truths of war.

As Franklin continues to preserve the history of its role in the Civil War through battlefield preservation, we should commend its citizens for their commitment to preserve the past. We must not forget what took place here. To do so would be a disservice to the memory of those who died on this hallowed ground.

Traci Nichols-Belt is the author of Onward Southern Soldiers: Religion and the Army of Tennessee in the Civil War, published by The History Press. Traci holds a Master's degree in public history from Middle Tennessee State University and a Bachelor's degree in Political Science from Anderson University. Her principal research interest is the Civil War, with a particular focus on the impact of religion on the military. Traci has appeared on radio and television to speak about the role of religion in the Civil War, and she has had her writings published in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly and in The New York Times Civil War blog, Disunion.

Five years after first publishing Traci’s book with The History Press, we remain grateful for the outpouring of support and interest we’ve received for Onward Southern Soldiers. It is a testament to the durability of her scholarship and to the passions readers have for her topic.

Franklin, of course, was once the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. At the Battle of Franklin in November of 1864, the Army of Tennessee lost over 6,000 dead and wounded, including six dead Confederate generals. Altogether, some 10,000 American soldiers became casualties at Franklin. When recollecting the battle years later one man said simply, “It was as if the devil had full possession of the earth.”

Following her talk, Traci took a self-guided tour of Franklin’s Civil War sites, including a brief walk along an area of Franklin once overrun by development. In the years that followed this bloody battle, the march of progress overtook portions of the battlefield. Commercial development consumed the land.

Concern for the loss of tangible remnants of the Battle of Franklin served as one of several factors that motivated Traci to pursue a degree in Public History. This shared concern also led the community of Franklin to preserve portions of the battlefield from the ravages of modernity.

Franklin now serves as a model for battlefield preservation throughout the nation. The citizens of Franklin deserve praise for their diligent work to restore these historic sites. The effort remains a work in progress, but after years of struggle, the results are beginning to pay off.

|

| The demolition of the Pizza Hut in 2005 (left) and the marker commemorating Patrick Cleburne's death as it appears today. Image and caption credit: The Civil War Trust. |

|

| This artist's rendering shows what a Battle of Franklin park will look like in the not-too-distant future. By purchasing land and removing commercial buildings, the citizens of Franklin have created a contiguous park allowing visitors to reflect on one Civil War's bloodiest episodes. Image and caption credit: The Civil War Trust. |

Times have changed dramatically since our nation’s earliest efforts to preserve Civil War memory. While Civil War monuments and the mythology of the “Lost Cause” continue to influence our narrative and shape public memory, they are no longer the sole source of remembrance.

Following the sesquicentennial anniversary of the war, a healthy debate has emerged from this period of commemoration concerning how best to present a more complete picture of the war and its primary cause—the institution of slavery. Still, society continues to struggle to come to grips with this “peculiar institution” and its legacy.

Battlefield preservation efforts like those taking place in Franklin provide us with an opportunity to learn. By asking difficult questions at the very site where conflict boiled over into battle, we move beyond the mere recitation of battlefield maneuvers and military strategy. We gain an opportunity to engage the public in a conversation about our shared Civil War memory by exploring the painful truths of war.

As Franklin continues to preserve the history of its role in the Civil War through battlefield preservation, we should commend its citizens for their commitment to preserve the past. We must not forget what took place here. To do so would be a disservice to the memory of those who died on this hallowed ground.

Traci Nichols-Belt is the author of Onward Southern Soldiers: Religion and the Army of Tennessee in the Civil War, published by The History Press. Traci holds a Master's degree in public history from Middle Tennessee State University and a Bachelor's degree in Political Science from Anderson University. Her principal research interest is the Civil War, with a particular focus on the impact of religion on the military. Traci has appeared on radio and television to speak about the role of religion in the Civil War, and she has had her writings published in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly and in The New York Times Civil War blog, Disunion.

"History is never true."

|

| Image credit: Wikimedia Commons |

History is never true. At no moment in the course of historical recording are all the facts known. The documents come to light serially, sporadically; all of them are never available at the same time. Centuries may elapse before the story of the World War is adequately told. A century, two centuries may pass before even a single movement or episode in a nation's history is understood.

Nor is it easy to arrive at the truth, even when all the essential factors in the historical problem or situation are ready to hand. For all history, as the great Italian critic, Benedetto Croce, has brilliantly pointed out, is contemporaneous. The writer, in dealing with times remote, interprets ideas, movements and events in the light of his own personal knowledge, experience and temperament. He cannot step off his own shadow. Even when he is writing of his own age and is strictly contemporaneous, he suffers the handicap of writing with insufficient data. History, written by a contemporary, is likely to be less accurate, less truthful than the history of the past written by someone living in the present.

If history is always contemporaneous and never true, there would seem to be no reason for its existence. The best excuse for the historical writer is that it is his function to correct the most glaring errors, to fill in the most yawning lacunae, in the writings of his predecessors. In so doing, he is giving a "new slant" to interpretation, or furnishing a new platform from which his successors may enter new fields of research.

-- Remarks by Archibald Henderson, "The Transylvania Company and the Founding of Henderson, K.Y.," delivered at the unveiling of six historical tablets at the Henderson Courthouse, October 11, 1929.

Gordon Belt is an information professional, archives advocate, public historian, and author of The History Press book, John Sevier: Tennessee's First Hero, which examines the life of Tennessee's first governor, John Sevier, through the lens of history and memory. On The Posterity Project, Gordon offers reflections on archives, public history, and memory from his home state of Tennessee.

Recollections of Watauga...

The month of July marks an important anniversary in the history of my home state of Tennessee. In July of 1776, settlers of the Holston, Watauga, and Nolichucky river valleys came under attack by Native American warriors led by the Cherokee Chief Old Abraham (or "Abram") of Chilhowee. Repulsed in the initial attack, the Cherokees besieged Fort Caswell on the Watauga (known also as Fort Watauga) for two weeks. John Sevier's defense of the fort, and the legends that followed, helped forge his reputation as a military leader and political force in the region. Following up on my earlier blog entry about William Tatham as an eyewitness to the Siege of Fort Watauga, I'd like to share a few more recollections of this important event in early Tennessee history...

Few contemporary accounts of the Siege of Fort Watauga survive. They do exist, however, for those who wish to find them. They remain buried deep within the manuscripts collected by the nineteenth-century antiquarian Lyman Draper, documented in Revolutionary War pension applications, and printed in the pages of early newspaper accounts. Tennessee's collective memory of the siege, however, rests firmly in the nostalgic prose of Dr. J. G. M. Ramsey's 1853 book, Annals of Tennessee. In his seminal work chronicling Tennessee's early history, Ramsey wistfully recalled his research visit to view the remnants of Fort Watauga. He wrote...

Ramsey considered his research visits to Elizabethton a pilgrimage. Watauga had captured Ramsey's imagination "with intense curiosity and almost with veneration." In his Annals of Tennessee, Ramsey declared Watauga "the abode and resting place of enterprise, virtue, hardihood, patriotism—the ancestral monument of real worth and genuine greatness." [Ramsey, 140-141]

Few recollections from the actual defenders of Fort Watauga eclipsed Ramsey's romantic narrative, yet two reports that surfaced less than one month after the attack echoed his patriotic sentiment.

An "Account of the Attack of Watauga Fort by the Cherokees," published in August of 1776, and widely circulated among newspapers of the period, revealed the following:

Further, "Intelligence from Williamsburgh, Virginia," published on August 16, 1776, detailed the depredations endured by the settlers prior to the Siege of Fort Watauga, and placed the Indian Wars in regional context, less than one month after the siege...

It is curious to note that not one of these reports specifically mention John Sevier's heroic defense of Fort Watauga, or Bonny Kate's dramatic rescue from her Cherokee pursuers in the moments preceding the siege. Yet, those stories endure in oral narratives and secondary accounts published years after the fact as key episodes in the drama of the Siege of Fort Watauga. In this season of independence, I offer these contemporary accounts as an act of remembrance of the Siege of Fort Watauga.

SELECTED SOURCES:

Gordon Belt is an information professional, archives advocate, public historian, and author of The History Press book, John Sevier: Tennessee's First Hero, which examines the life of Tennessee's first governor, John Sevier, through the lens of history and memory. On The Posterity Project, Gordon offers reflections on archives, public history, and memory from his home state of Tennessee.

Few contemporary accounts of the Siege of Fort Watauga survive. They do exist, however, for those who wish to find them. They remain buried deep within the manuscripts collected by the nineteenth-century antiquarian Lyman Draper, documented in Revolutionary War pension applications, and printed in the pages of early newspaper accounts. Tennessee's collective memory of the siege, however, rests firmly in the nostalgic prose of Dr. J. G. M. Ramsey's 1853 book, Annals of Tennessee. In his seminal work chronicling Tennessee's early history, Ramsey wistfully recalled his research visit to view the remnants of Fort Watauga. He wrote...

"The spot is easily identified by a few graves and the large locust tree standing conspicuously on the right of the road leading to Elizabethton. Let it ever be a sacrilege to cut down that old locust tree – growing, as it does, near the ruins of the Watauga fort which sheltered the pioneer and protected his family."

Ramsey considered his research visits to Elizabethton a pilgrimage. Watauga had captured Ramsey's imagination "with intense curiosity and almost with veneration." In his Annals of Tennessee, Ramsey declared Watauga "the abode and resting place of enterprise, virtue, hardihood, patriotism—the ancestral monument of real worth and genuine greatness." [Ramsey, 140-141]

|

| Watauga Fort Marker Image credit: The Historical Marker Database |

Few recollections from the actual defenders of Fort Watauga eclipsed Ramsey's romantic narrative, yet two reports that surfaced less than one month after the attack echoed his patriotic sentiment.

An "Account of the Attack of Watauga Fort by the Cherokees," published in August of 1776, and widely circulated among newspapers of the period, revealed the following:

Williamsburgh, Virginia, August 10, 1776.

A correspondent has favoured us with extracts of letters from officers of rank in Fincastle, from which we learn, that on Sunday, the 21st of July, a large party of Indians attacked the Watauga Fort, in which were one hundred and fifty men. They fired on a great number of women, who went out at daybreak to milk their cows, and chased them into the fort, but providentially did not kill one of them.

They fired briskly on the fort till eight o' clock, but without effect, and then retired, with considerable loss, as was supposed from the quantity of blood found; but they returned to the attack, and were besieging the fort six days after, as a messenger, who was slipped out, informed our men on Holstein. A detachment was sent to relieve the fort, and it was expected they would do so on Monday, the 29th. A party of one hundred men of the Militia fell in with a party of forty Cherokees, who were fifty miles on this side the Island, at one of the deserted plantations, and killed five, took one prisoner, and twenty guns.

It is worthy of our observation, that in these several skirmishes with the Indians, in all of which we did more execution than in some of the principal actions of the last war, we lost not a man. No one can reflect on this, and many other circumstances which have attended the present war with the British tyrant, without acknowledging that he sees evident proofs of the Divine interposition in our favour. [LINK]

|

| The Fort Watauga reconstruction at Sycamore Shoals State Historic Park. The original fort was built in the mid-1770s to protect the Watauga settlers from Cherokee attacks. The fort was reconstructed in the 1970s based on archaeological evidence and the design of contemporary Appalachian frontier forts. Image and caption credit: Wikimedia Commons. |

Further, "Intelligence from Williamsburgh, Virginia," published on August 16, 1776, detailed the depredations endured by the settlers prior to the Siege of Fort Watauga, and placed the Indian Wars in regional context, less than one month after the siege...

Williamsburgh, August 16, 1776.

On Tuesday, the 13th instant, the First Virginia Regiment in the Continental service marched from this city for New York. From undoubted authority we can assure the publick that fifteen thousand weight of pure lead have been got from our mines in the back country, which, after being cast into bullets, we hope will be unerringly directed against our enemies.

The last advices from the back country are, that the Cherokee and Creek Indians, to the number of between six and seven hundred, are encamped in Carter's valley, from whence they send out parties against the settlements, some of which had penetrated near one hundred miles on this side of the Big Island, carrying destruction wherever they come, by burning houses, fences, fields of wheat and other grain, and turning droves of horses into the corn-fields. Upwards of one thousand head of horses have been driven off, and a great number of cattle; the sheep and hogs they shoot down. They have killed and scalped eighteen men, one or two women, and several children; some of the people were most barbarously murdered, too shocking to relate.

The ruined settlers had collected themselves together at different places, and forted themselves, four hundred and upwards at Major Shelby' s, about the same number at Captain Campbell's, and a considerable number at Amos Eaton' s. The fort at Watauga, which was besieged by four hundred savages, are now relieved, the Indians having abandoned their enterprise upon the approach of Colonel Russell, with about three hundred men. In all the skirmishes with the Indians our people have continually worsted them, and, in the whole, have killed and scalped twenty-seven, and badly wounded many others, as was discovered by the tracks of blood. A man from the frontiers of Georgia had arrived in Fincastle, who declared upon oath, that he saw upwards of one hundred people buried in one day, who were killed by the Creek Indians.

By an express from Colonel Russell, of Fincastle, we learn, that on his approaching the Watauga Fort with the men under his command, the Indians retired precipitately; however, not without losing one man, and having two wounded, by a party that pursued them. The fort was thus fortunately relieved after a fortnight's close siege, during the greater part of which time our people lived on parched corn. There were supposed to be five hundred women and children in this little fort, who fled there for shelter on hearing that the Indians were marching into that part of the country. We lost not a man in this long affair, except four or five who ventured out to drive in some cows; these were found scalped.

The number of Indians concerned in the different ravages lately committed in Fincastle amount to six or seven hundred, some say eight hundred; and yet, sudden as their attack was, they murdered in all their butchering parties but eighteen persons, and wounded six, whilst our men killed in the skirmishes with them twenty-six on the spot, (as many were carried off dead,) took one prisoner, and wounded at least as many as they killed. As the Cherokees have been so completely checked in their career, and we understand from Fort Pitt that the Northern Indians are not disposed to attack us in that quarter, and have only engaged not to suffer us to march through their country against Detroit, we may hope that there is not much to be dreaded from the terrible combination of Indians we have been threatened with by our enemies. [LINK]

It is curious to note that not one of these reports specifically mention John Sevier's heroic defense of Fort Watauga, or Bonny Kate's dramatic rescue from her Cherokee pursuers in the moments preceding the siege. Yet, those stories endure in oral narratives and secondary accounts published years after the fact as key episodes in the drama of the Siege of Fort Watauga. In this season of independence, I offer these contemporary accounts as an act of remembrance of the Siege of Fort Watauga.

SELECTED SOURCES:

- J. G. M. Ramsey. Annals of Tennessee, pp. 140-141+

- American Archives, ed., Peter Force. Available online, courtesy of Northern Illinois University Library, http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/.

Gordon Belt is an information professional, archives advocate, public historian, and author of The History Press book, John Sevier: Tennessee's First Hero, which examines the life of Tennessee's first governor, John Sevier, through the lens of history and memory. On The Posterity Project, Gordon offers reflections on archives, public history, and memory from his home state of Tennessee.

William Tatham, Wataugan

As Sycamore Shoals State Historic Park prepares to celebrate its annual observance of the Siege of Fort Watauga (or more accurately, Fort Caswell), I thought the occasion offered an appropriate moment to reflect upon the recollections of one of the fort's original defenders, William Tatham.

William Tatham (1752-1819), the eldest of five children born in England, emigrated to Virginia in 1769. Upon his arrival, he found employment as a clerk with the mercantile firm of Carter & Trent, merchants operating on the James River. Tatham spent many hours during his years of service with Carter & Trent listening to the wild and fascinating tales of the longhunters who frequented the Virginia wilderness. He sought the same sense of adventure for his own life, and by 1774, the lure of the frontier brought Tatham to Watauga. There he later witnessed the Cherokee siege of Fort Caswell in the summer of 1776.

The Cherokees besieged the fort for two solid weeks leaving its inhabitants short on food and supplies. John Sevier, James Robertson, and their fellow defenders held off the Cherokee assault and awaited reinforcements, but by the time that they arrived, the Cherokees had already abandoned their attack.

The siege at Fort Caswell on the Watauga is an episode of Tennessee history wrapped in myth and memory. In the years that followed, oral traditions, repeated by succeeding generations and validated by the published accounts of late-nineteenth century antiquarians and storytellers, embellished the details of this engagement with each telling. These authors recalled the tale of John Sevier's rescue of Catherine "Bonny Kate" Sherrill at Fort Caswell, in particular, with literary flair.

In his Annals of Tennessee, Dr. J. G. M. Ramsey chronicled Sevier's "determined bravery" in helping to defend the fort, and in his book, Rear-Guard of the Revolution, James Gilmore described how Sevier courageously faced down "two or three hundred savages" as a young "Bonny Kate" ran from her Cherokee pursuers and into the arms of her rescuer.

Decades later, as the jurist and antiquarian Samuel Cole Williams began compiling research notes for a book about the Lost State of Franklin, he learned that Tatham had been a witness to the Siege of Fort Caswell. Inspired by this story, Williams published a thin biography in 1922 entitled, William Tatham, Wataugan. He later published a revised, though still brief, edition of his Tatham biography in 1947.

According to Williams, Tatham was "the only defender of Fort Caswell who wrote reminiscences of occurrences during that early invasion." Despite his close proximity to the event itself, Tatham's account of the Siege at Fort Caswell revealed his own embellishments, and Tatham likely overstated his role in defending the fort. Nevertheless, Williams "made liberal use of Tatham's writings" in his own works, including History of the Lost State of Franklin, Dawn of Tennessee Valley and Tennessee History, and Tennessee During the Revolutionary War, among numerous other titles.

Tatham's full account of the Siege of Fort Caswell originally appeared in the April 6, 1793 edition of the Knoxville Gazette. Williams later published Tatham's account in his book, William Tatham, Wataugan. This is William Tatham's story:

William Tatham, Wataugan by Samuel Cole Williams is available in most public or university libraries, and may be purchased through any number of used book stores or antiquarian book dealers.

Gordon Belt is an information professional, archives advocate, public historian, and author of The History Press book, John Sevier: Tennessee's First Hero, which examines the life of Tennessee's first governor, John Sevier, through the lens of history and memory. On The Posterity Project, Gordon offers reflections on archives, public history, and memory from his home state of Tennessee.

William Tatham (1752-1819), the eldest of five children born in England, emigrated to Virginia in 1769. Upon his arrival, he found employment as a clerk with the mercantile firm of Carter & Trent, merchants operating on the James River. Tatham spent many hours during his years of service with Carter & Trent listening to the wild and fascinating tales of the longhunters who frequented the Virginia wilderness. He sought the same sense of adventure for his own life, and by 1774, the lure of the frontier brought Tatham to Watauga. There he later witnessed the Cherokee siege of Fort Caswell in the summer of 1776.

The Cherokees besieged the fort for two solid weeks leaving its inhabitants short on food and supplies. John Sevier, James Robertson, and their fellow defenders held off the Cherokee assault and awaited reinforcements, but by the time that they arrived, the Cherokees had already abandoned their attack.

The siege at Fort Caswell on the Watauga is an episode of Tennessee history wrapped in myth and memory. In the years that followed, oral traditions, repeated by succeeding generations and validated by the published accounts of late-nineteenth century antiquarians and storytellers, embellished the details of this engagement with each telling. These authors recalled the tale of John Sevier's rescue of Catherine "Bonny Kate" Sherrill at Fort Caswell, in particular, with literary flair.

In his Annals of Tennessee, Dr. J. G. M. Ramsey chronicled Sevier's "determined bravery" in helping to defend the fort, and in his book, Rear-Guard of the Revolution, James Gilmore described how Sevier courageously faced down "two or three hundred savages" as a young "Bonny Kate" ran from her Cherokee pursuers and into the arms of her rescuer.

|

| "Siege of Fort Watauga." An artist's sketch of Catherine "Bonny Kate" Sherrill's escape from Cherokee pursuers. Image credit: Tennessee State Library and Archives |

Decades later, as the jurist and antiquarian Samuel Cole Williams began compiling research notes for a book about the Lost State of Franklin, he learned that Tatham had been a witness to the Siege of Fort Caswell. Inspired by this story, Williams published a thin biography in 1922 entitled, William Tatham, Wataugan. He later published a revised, though still brief, edition of his Tatham biography in 1947.

According to Williams, Tatham was "the only defender of Fort Caswell who wrote reminiscences of occurrences during that early invasion." Despite his close proximity to the event itself, Tatham's account of the Siege at Fort Caswell revealed his own embellishments, and Tatham likely overstated his role in defending the fort. Nevertheless, Williams "made liberal use of Tatham's writings" in his own works, including History of the Lost State of Franklin, Dawn of Tennessee Valley and Tennessee History, and Tennessee During the Revolutionary War, among numerous other titles.

Tatham's full account of the Siege of Fort Caswell originally appeared in the April 6, 1793 edition of the Knoxville Gazette. Williams later published Tatham's account in his book, William Tatham, Wataugan. This is William Tatham's story:

In January 1776 emigration had advanced over the Indian boundary as far as Big Creek on the north side of Holston and to Big Limestone Creek on the south side, but these settlers were under no legal or regular government.

Added to this there were a number of people called Regulators, who had fled from North Carolina to the extreme frontier for safety after their battle against Governor Tryon at the Alamance and were actually about joining the Cherokees against the Americans. To make the matter still worse, while the Indians were on their invasion, the chief stock of powder was but six pounds in the hands of the settlers [on the Watauga].

In this dilemma, the Virginia government gave orders for all men to retire within the line or they would be treated as outlaws. The people on the north side of the Holston obeyed the mandate; but through the influence, in a great degree, of William Cocke, Esq., they forted themselves at Amos Heaton’s [Eaton’s] now [1793] Sullivan Old Court House; and those on the Watauga and Nolichucky posted [at the latter] about thirty volunteers under Captain James Robertson, just above the mouth of Big Limestone, where Mr. Gillespie now lives.

Shortly after this party took post and before they had finished their fort, called Fort Lee, four of the traders made their escape from the Cherokee nation and apprised them of the immediate march of about six hundred Cherokees and a few Creeks, who were destined against the settlements. The inhabitants immediately took the alarm, and instead of flocking to the frontier barrier on strong and open ground, thereby covering their country, those on the Nolachucky hastily fled, carrying off their livestock and provisions leaving about fifteen of the volunteers at the frontier to make the best shift in their power.

The result of this precipitate retreat was this: The few who were determined to oppose the enemy in the defense of that quarter were joined by as many in the rear of the scamper as had not time to get safely off: and were thus compelled to fortify near the Sycamore Shoals of Watauga, on much weaker ground than that which they had evacuated: cut off from assistance and resources [from North Carolina] by the mountains and defiles which were at that day almost impenetrable; and from every possibility of information, save for their own vigilance.

The party at Heaton’s fort were nearly in a similar situation; and these two posts, weak as new settlements could be, had to stand the brunt of the enemy whose numbers, prowess, resources and European patronage was at least equal to any danger that we now dread at this day. On the southern and western side of Donelson’s line we were obliged to rely upon the following numbers for defense against both southern and northern Indians, as near as I can recollect.

At Watauga, men, boys and negroes fit to bear arms, but not well armed, under Captain James Robertson. Yet the country was well defended! And strange as it may appear this territory [Southwest] owes its present consequence to this handful of men; for in less than two years after, the Tennessee and Kentucky countries contained no less than fifty-seven forts. It is very probable that if this small party had given way, the people would have generally (if not all) fled to the eastern side of the Allegheny mountains.

|

| A recreation of Fort Caswell (a.k.a. Fort Watauga). Image credit: Sycamore Shoals State Historic Park. |

William Tatham, Wataugan by Samuel Cole Williams is available in most public or university libraries, and may be purchased through any number of used book stores or antiquarian book dealers.

Gordon Belt is an information professional, archives advocate, public historian, and author of The History Press book, John Sevier: Tennessee's First Hero, which examines the life of Tennessee's first governor, John Sevier, through the lens of history and memory. On The Posterity Project, Gordon offers reflections on archives, public history, and memory from his home state of Tennessee.

Sowing the seeds of war: The Yellow Creek Massacre and the Battle of Point Pleasant

Today, my ongoing research into the origins of the Battle of Point Pleasant and John Sevier's role in it takes me to the reminiscences of Judge Henry Jolly. In 1849, a man named S. P. Hildreth interviewed Jolly on Lyman Draper's behalf for Draper's ongoing research into the border wars of the Old Southwest. In Hildreth's recorded transcript of the interview, Jolly recalled his memories of the "Yellow Creek Massacre," an event which ultimately led Lord Dunmore to bring the might of the Virginia militia to bear upon the native people of the region. *

The broad brushstrokes of history have judged that Dunmore's overwhelming victory over Chief Cornstalk's Indian alliance in the 1774 Battle of Point Pleasant came as a consequence of depredations perpetrated by a "Savage Empire." A careful examination of Jolly's recollections, however, reveals the root cause of the conflict -- a cause bathed in the blood of vengeance.

The Mingo Indian chief known to the white people as "John Logan" sought revenge for the brutal murder of his family by white settlers at Yellow Creek on April 30, 1774. Jolly, a respected jurist, was sixteen years old at the time of the massacre, yet at the age of 75, he recalled the savage incident which led to the Battle of Point Pleasant in striking detail:

Jolly's memory of the Yellow Creek Massacre and the events that followed failed to recall the details of the savage attack on Logan's kin. Others would testify to witnessing a horrific scene in which members of the Greathouse party not only kidnapped a young child and brutally murdered all the natives, but they also mutilated their bodies and disemboweled Logan's pregnant sister. They then scalped and impaled her unborn child on a stake. During the slaughter, one of the attackers cruelly bragged, "Many a deer have I served in this way."

In his grief, Logan called out to the men whom he accused of murdering his family:

The Yellow Creek Massacre ended all hope Chief Cornstalk had for a peaceful coexistence with the settlers as Logan sought revenge for the brutal slayings. Logan later lamented:

In a letter to Colonel William Preston, Major Arthur Campbell urgently pleaded for military intervention. In his letter, Campbell communicated the frequency of Logan's vengeance-fueled assault on the settlers. "So many attacks in so short a time, give the inhabitants very alarming apprehensions," he wrote.

Lord Dunmore answered Campbell's call for reinforcements and exacted his own form of revenge for Logan's personal pursuit of justice, ultimately defeating Cornstalk's Indian warriors at the Battle of Point Pleasant. Although Logan did not participate in the battle itself, he did continue to fight against the Americans in the Revolutionary War. He escaped death until 1780, when ironically, a member of his own family, a nephew, murdered Logan near present-day Detroit, Michigan.

PREVIOUS POSTS:

SELECTED SOURCES:

NOTES:

Gordon Belt is an information professional, archives advocate, public historian, and author of The History Press book, John Sevier: Tennessee's First Hero, which examines the life of Tennessee's first governor, John Sevier, through the lens of history and memory. On The Posterity Project, Gordon offers reflections on archives, public history, and memory from his home state of Tennessee.

The broad brushstrokes of history have judged that Dunmore's overwhelming victory over Chief Cornstalk's Indian alliance in the 1774 Battle of Point Pleasant came as a consequence of depredations perpetrated by a "Savage Empire." A careful examination of Jolly's recollections, however, reveals the root cause of the conflict -- a cause bathed in the blood of vengeance.

The Mingo Indian chief known to the white people as "John Logan" sought revenge for the brutal murder of his family by white settlers at Yellow Creek on April 30, 1774. Jolly, a respected jurist, was sixteen years old at the time of the massacre, yet at the age of 75, he recalled the savage incident which led to the Battle of Point Pleasant in striking detail:

In the Spring of the year 1774 a party of Indians encamped on the Northwest of the Ohio, near the mouth of Yellow Creek. A party of whites called Greathouse’s party, lay on the opposite side of the river. The Indians came over to the white party—I think five men, one woman and an infant babe. The whites gave them rum, which three of them drank, and in a short time became very drunk. The other two men and the woman refused. The sober Indians were challenged to shoot at a mark, to which they agreed, and as soon as they emptied their guns, the whites shot them down. The woman attempted to escape by flight, but was also shot down. She lived long enough, however, to beg mercy for her babe, telling them that it was a kin to themselves. They had a man in the cabin, prepared with a tomahawk for the purpose of killing the three drunk Indians, which was immediately done. The party of men, women &c moved off for the interior settlements, and came to Catfish Camp on the evening of the next day, where they tarried until the next day. I very well recollect my mother, feeding and dressing the babe, chirping to the little innocent, and it smiling, however, they took it away, and talked of sending it to its supposed father, Col. Geo. [John] Gibson of Carlisle (Pa.) who was then [and] had been for several years a trader amongst the Indians.

|

| An illustration depicting the Yellow Creek Massacre. Image credit: West Virginia Encyclopedia. |

The remainder of the party, at the mouth of Yellow Creek, finding that their friends on the opposite side of the river was massacred, the[y] attempted to escape by descending the Ohio, and in order to avoid being discovered by the whites, passed on the west side of Wheeling Island, and landed at pipe creek, a small stream that empties into the Ohio a few miles below Graves Creek, where they were overtaken by Cresap with a party of men from Wheeling. They I believe carried him in a litter from Wheeling to Redstone. I saw the party on the return from their victorious campaign.

The Indians had for some time before this event thought themselves intruded upon by the Long Knife, as they called the Virginians at that time, and many of them were for war—however the[y] called a Council, in which Logan acted a conspicuous part. He admitted their ground of complaint, but at the same time reminded them of some aggressions on the part of the Indians, and that by a war, they could but harass and distress the frontier settlements for a short time, that the Long Knife would come like the trees in the woods, and that ultimately, they would be drove from their good land that they now possessed. He therefore strongly recommended peace. To him they all agreed, grounded the hatchet, every thing wore a tranquil appearance, when behold, in came the fugitives from Yellow Creek; Logan’s father, Brother and sister murdered. What is to be done now? Logan has lost three of his nearest and dearest relations, the consequence is that this same Logan, who a few days before was so pacific, raises the hatchet, with a declaration, that he will not ground it, until he has taken ten for one, which I believe he completely fulfilled, by taking thirty scalps and prisoners in the summer of 74. The above has often been told to me by sundry persons who was at the Indian town, at the time of the Council alluded to, and also when the remains of the party came in from Yellow Creek; Thomas Nicholson has told me the above and much more, another person (whose name I cannot recollect) told me that he was at the towns when the Yellow Creek Indians came it, that there was a very Great lamentation by all the Indians of that places, some friendly Indian advised him to leave the Indian Settlement, which he did.

Could any person of common rationality, believe for a moment, that the Indians came to Yellow Creek with hostile intention, or that they had any suspicion of the whites, having any hostile intentions against them? Would five men have crossed the river, three of them in a short time dead drunk, the other two discharging their guns, putting themselves entirely at the mercy of the whites, or would they have brought over a squaw, with an infant papoose, if they had not reposed the utmost confidence in the friendship of the whites? Every person who is acquainted with Indians knows better, and it was the belief of the inhabitants who were capable of reasoning on the subject, that all the depredations committed on the frontiers was by Logan and his party, as a retaliation, for the murder of Logan’s friends at Yellow Creek—I mean all the depredations committed in the year 1774.

Jolly's memory of the Yellow Creek Massacre and the events that followed failed to recall the details of the savage attack on Logan's kin. Others would testify to witnessing a horrific scene in which members of the Greathouse party not only kidnapped a young child and brutally murdered all the natives, but they also mutilated their bodies and disemboweled Logan's pregnant sister. They then scalped and impaled her unborn child on a stake. During the slaughter, one of the attackers cruelly bragged, "Many a deer have I served in this way."

In his grief, Logan called out to the men whom he accused of murdering his family:

"What did you kill my people on Yellow Creek for. The white People killed my kin at Coneestoga a great while ago, & I though[t nothing of that]. But you killed my kin again on Yellow Creek, and took m[y cousin prisoner] then I thought I must kill too; and I have been three time[s to war since but] the Indians is not Angry only myself."

Captain Joh[n Logan] July 21st. Day.

The Yellow Creek Massacre ended all hope Chief Cornstalk had for a peaceful coexistence with the settlers as Logan sought revenge for the brutal slayings. Logan later lamented:

"I appeal to any white man to say if he ever entered Logan's cabin hungry, and he gave him not meat; if he ever came cold and naked and he clothed him not. During the course of the last long and bloody war, Logan remained idle in his cabin, an advocate for peace.... There runs not a drop of my blood in the veins of any living creature. This has called on me for revenge. I have sought it; I have killed many; I have fully glutted my vengeance. For my country, I rejoice in the beams of peace."

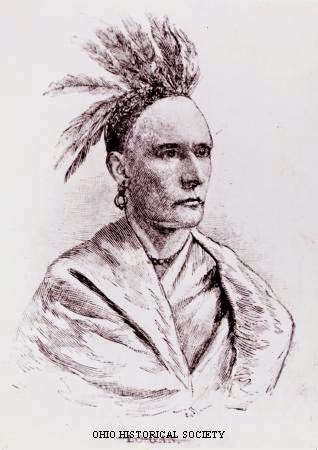

|

| Photographic reproduction of a print depicting John Logan (1725-1780), a chief of the Mingo tribe. Image credit: Ohio History Central. |

In a letter to Colonel William Preston, Major Arthur Campbell urgently pleaded for military intervention. In his letter, Campbell communicated the frequency of Logan's vengeance-fueled assault on the settlers. "So many attacks in so short a time, give the inhabitants very alarming apprehensions," he wrote.

Lord Dunmore answered Campbell's call for reinforcements and exacted his own form of revenge for Logan's personal pursuit of justice, ultimately defeating Cornstalk's Indian warriors at the Battle of Point Pleasant. Although Logan did not participate in the battle itself, he did continue to fight against the Americans in the Revolutionary War. He escaped death until 1780, when ironically, a member of his own family, a nephew, murdered Logan near present-day Detroit, Michigan.

PREVIOUS POSTS:

SELECTED SOURCES:

- "Reminiscences of Judge Henry Jolly," Draper Manuscripts, 6NN22-24, cited in Reuben Gold Thwaites and Louise Phelps Kellogg, Documentary History of Dunmore's War, 1774. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1905, pp. 9-14.

- Colin G. Calloway. The Shawnees and the War for America. New York: Viking, 2007, pp. 51-52.

- Thomas Swift Landon. "Greathouse Party Massacre." e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. August 13, 2012.

- "Logan's Lament (Transcript)." Ohio History Central.

NOTES:

*

According to Thwaites' Documentary History of Dunmore's War, 9n16: “The following was sent to Dr. Draper in 1849, by S. P. Hildreth, who had an interview with Judge Jolly. The latter was sixteen years of age at the time

of these occurrences, and recollected them well. There has been much

controversy over these incidents; for the statements of other contemporaries,

see Sappington, in Jefferson’s Notes on

Virginia (ed. of 1825), pp. 336-339; Tomlinson, in Jacob’s Cresap, pp. 133-137; George Rogers

Clark’s letter, ibid., pp. 154-158; Washington-Crawford Letters, pp. 86, 87;

and N. Y. Colon. Docs., viii, pp.

463-465.—Ed.”

Gordon Belt is an information professional, archives advocate, public historian, and author of The History Press book, John Sevier: Tennessee's First Hero, which examines the life of Tennessee's first governor, John Sevier, through the lens of history and memory. On The Posterity Project, Gordon offers reflections on archives, public history, and memory from his home state of Tennessee.

"You may judge that we had a very hard day." -- Isaac Shelby and the Battle of Point Pleasant

In my previous post on The Posterity Project, I examined how, at the turn of the twentieth century, the archivist and historian Virgil Lewis chronicled the Battle of Point Pleasant, a pivotal engagement that occurred on October 10, 1774. The battle pitted a confederation of Indian tribes against the Virginia militia during Lord Dunmore's War. In a struggle for control over an area of land now comprised of portions of West Virginia and Kentucky, this bloody confrontation gave John Sevier his first taste of battle with the Indians and helped shape his philosophy of offensive guerrilla warfare for years to come.

|

| An artist's illustration of the Battle of Point Pleasant. Image credit: West Virginia Division of Culture & History |

Lewis and other historians of the battle credited Lieutenant Isaac Shelby with leading the charge toward victory with a flanking maneuver that ultimately turned the tide of the battle in the Virginian's favor. Shelby chronicled his experience as a witness and participant in the Battle of Point Pleasant in a letter to his uncle, John Shelby, written just six days after the battle on October 16, 1774. In his book, History of the Battle of Point Pleasant, Lewis remarked that Isaac Shelby's account was regarded by historians as "the best of

all that was written on the field."

The following text is Isaac Shelby’s letter to his uncle describing the Battle of Point Pleasant in all its vivid detail, with only a few minor copy edits made to correct for errors in spelling, punctuation and grammar…

Dear Uncle,

I gladly embrace this opportunity to acquaint you that we are all three [Capt. Evan Shelby, and his two sons, Isaac and James] yet alive through God's mercies, and I sincerely wish that this may find you and your family in the station of health that we left you. I never had anything worth notice to acquaint you with since I left you til now. The Express seems to be hurrying that I can't write you with the same coolness and deliberation as I would.

We arrived at the mouth [of] Kanawha Thursday 6th October and encamped on a fine piece of ground with an intent to wait for the Governor and his party, but hearing that he was going another way we contented ourselves to stay there a few days to rest the troops, &c when we looked upon ourselves to be in safety til Monday morning the 10th instant when two of our companies went out before day to hunt, To wit Valentine Sevier and James Robertson, and discovered a party of Indians. As I expect you will hear something of our battle before you get this I have here stated this affair nearly to you.

For the satisfaction of the people in your parts in this they have a true state of the memorable battle fought at the mouth of the great Kanawha on the 10th instant. Monday morning, about half an hour before sunrise, two of Captain Russell's Company discovered a large party of Indians about a mile from camp, one of which men was shot down by the Indians, the other made his escape and brought intelligence.[1]

In two or three minutes after, two of Captain [Evan] Shelby's came in and confirmed the account. General Andrew Lewis being informed thereof, immediately ordered out Colonel Charles Lewis to take the command of one hundred and fifty of the Augusta Troops, and with him went Captain Dickinson, Captain Harrison, Captain Wilson, Captain John Lewis, of Augusta, and Captain Lockridge, which made the first Division. Colonel Fleming was also ordered to take the command of one hundred and fifty more of the Botetourt, Bedford, and Fincastle Troops, viz: Captain Thomas Buford, from Bedford, Captain Love, of Botetourt, Captain Shelby and Captain Russell, of Fincastle, which made the second Division. Colonel Charles Lewis's Division marched to the right some distance from the Ohio; and Colonel Fleming, with his Division, on the bank of the Ohio, to the left. Colonel Charles Lewis's Division had not marched quite half a mile from camp, when about sunrise, an attack was made on the front of his Division, in a most vigorous manner by the United tribes of Indians—Shawnees; Delawares, Mingoes, Taways, and several other Nations in number not less than eight hundred and by many thought to be a thousand.

In this heavy attack Colonel Charles Lewis received a wound which soon after caused his death and several of his men fell on the spot in fact the Augusta Division was forced to give way to the heavy fire of the enemy. In about a second of a minute after the attack on Colonel Lewis’s Division the enemy engaged the front of Colonel Fleming’s Division on the Ohio, and in a short time Colonel Fleming received two balls through his left arm and one through his breast, and after animating the captains and soldiers in a calm manner to the pursuit of victory, returned to camp.[2]

The loss of the brave Colonels was sensibly felt by the officers in particular, but the Augusta troops being shortly reinforced from camp by Colonel Field with his Company together with Captain McDowell, Captain Mathews and Captain Stuart from Augusta, Captain John Lewis, Captain Paulin, Captain Arbuckle and Captain McClanahan from Botetourt, the enemy no longer able to maintain their ground was forced to give way til they were in a line with the troops left in action on banks of Ohio, by Colonel Fleming. In this precipitate retreat Colonel Field was killed, after which Captain [Evan] Shelby was ordered to take the Command.

During this time which was til after twelve o'clock, the action continued extremely hot, the close underwood many steep banks and logs greatly favored their retreat, and the bravest of their men made the use of themselves, whilst others were throwing their dead into the Ohio and carrying off their wounded. After twelve the action in a small degree abated but continued sharp enough til after one o’clock. Their long retreat gave them a most advantageous spot of ground, from whence it appeared to the officers so difficult to dislodge them that it was thought most advisable to stand as the line then was formed which was about a mile and a quarter in length, and had til then sustained a constant and equal weight of fire from wing to wing.

It was til half an hour of sunset they continued firing on us which we returned to their disadvantage at length night coming on they found a safe retreat. They had not the satisfaction of scalping any of our men save one or two stragglers whom they killed before the engagement many of their dead they scalped rather than we should have them, but our troops scalped upwards of twenty of those who were first killed. It is beyond doubt their loss in number far exceeds ours, which is considerable… about 46 killed and about 80 wounded. From this, Sir, you may judge that we had a very hard day.[3]

It is really impossible for me to express or you to conceive the conditions that we were under, sometimes, the hideous cries of the enemy and the groans of our wounded men lying around was enough to shudder the stoutest heart. It is the general opinion of the officers that we shall soon have another engagement as we have now got over into the enemy’s country. We expect to meet the Governor about forty or fifty miles from here. Nothing will save us from another battle unless they attack the Governor’s Party. Five men that came in daddy's company were killed. I don't know that you were acquainted with any of them except Marck Williams who lived with Roger Top. Acquaint Mr. Carmack that his son was slightly wounded through the shoulder and arm and that he is in a likely way of recovery. We leave him at the mouth of Kanawha and one very careful hand to take care of him. There is a garrison and three hundred men left at that place with a surgeon to heal the wounded. We expect to return to the garrison in about sixteen days from the Shawnee towns.

I have nothing more particular to acquaint you with concerning the battle. As to the country, I can't now say much in praise of any that I have yet seen. Daddy intended writing to you but did not know of the Express til the time was too short. I have wrote to Mammy though not so fully as to you as I then expected the Express was just going. We seem to be all in a moving posture, just going from this place so that I must conclude wishing you health and prosperity til I see you and your family. In the meantime, I am your truly affectionate friend and humble servant.

-- Isaac Shelby

|

| Portrait of Isaac Shelby (1750–1826), the first and fifth Governor of Kentucky, ca. 1820. Image credit: Kentucky Historical Society |

SELECTED SOURCES:

- Virgil A. Lewis. History of the Battle of Point Pleasant Fought Between White Men and Indians at the Mouth of the Great Kanawha River. Charleston, WV: The Tribune Printing Company, 1909, pp. 43-45.

- Reuben Gold Thwaites and Louise Phelps Kellogg, eds. Documentary History of Dunmore's War, 1774. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1905, pp. 269-277.

- Philip Sturm, "Battle of Point Pleasant." e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. March 2, 2015.

NOTES:

- [1] These were Joseph Hughey, of Shelby’s company, and James Mooney, of Russell’s. The former was killed by a white renegade, Tavenor Ross, while the latter brought the news to camp. Mooney was a former neighbor of Daniel Boone, upon the Yadkin in North Carolina, and had accompanied him upon the disastrous Kentucky hunting expedition of 1769. He was killed at Point Pleasant.

- [2] According to Samuel G. Drake’s History and Biography of the Indians of North America, Book V., p. 43, “Fleming was a heroic officer; after two balls had passed through his arm, he continued on the field, and exercised his command with the greatest coolness and presence of mind. His voice was continually heard, ‘Don’t lose an inch of ground; advance; outflank the enemy; keep between them and the river.’ This was his last command; there came a shot which passed through his lungs and he fell, but insisted still to be permitted to remain upon the field. As he was borne from the field a portion of the lung protruded from the wound, and he pressed it back with his own hand.” Although he survived the battle, Fleming never fully recovered from his wounds. His disabilities prevented his military service in the Revolutionary War, yet he went on to serve his country in another role, as a member of the First Senate of the Commonwealth of Virginia and later as the acting Governor of the Commonwealth. Colonel Fleming died on August 5, 1795 at the age of sixty-six, “and carried to his grave, in his body, a bullet received at the Battle of Point Pleasant.” See: Lewis, History of the Battle of Point Pleasant, 44n5 and 25n4. See also: William D. Hoyt, Jr., “Colonel William Fleming in Dunmore’s War, 1774,” West Virginia History, 3:2 (Jan. 1942), 99-119.

- [3] According to Lewis, "The number of Indians killed and wounded could never be known for they were continually carrying off their dead and throwing them into the river... His loss has been stated at two hundred and thirty-three." In a footnote, Lewis also observed, "Pu-kee-she-no a Shawnee, whose name signified 'I light from flying' was killed in the battle. He was the noblest warrior that perished there. His wife was a Cherokee woman whose name was Mee-thee-ta-she, which signified 'a turtle laying her eggs in the sand.' These were the parents of Tecumseh and his brothers Ells-wat-a-wa one who foretells; otherwise the Prophet, and Kum-sha-ka, signifying 'A tiger that flies in the air.' The mother is said to have transplanted the beautiful Cherokee rose from the banks of the Tennessee to those of the Scioto, whence it has spread far and wide. Their home was on the banks of that river, on the site of the present city of Chilicothe, and there the little son, Tecumseh, but six years of age, played while his father was killed at Point Pleasant.” See: Lewis, History of the Battle of Point Pleasant, 51n11, and Drake, Biography and History of the Indians of North America, Book V., p.123.

Gordon Belt is an information professional, archives advocate, public historian, and author of The History Press book, John Sevier: Tennessee's First Hero, which examines the life of Tennessee's first governor, John Sevier, through the lens of history and memory. On The Posterity Project, Gordon offers reflections on archives, public history, and memory from his home state of Tennessee.

The Battle of Point Pleasant and Virgil Lewis' fight against "Manufactured History"

Book Review: History of the Battle of Point Pleasant by Virgil A. Lewis. Charleston, WV: The Tribune Printing Company, 1909.

In the "Prefatory Note" to his 1909 work, History of the Battle of Point Pleasant, Virgil Anson Lewis described growing up "within a few miles of the battlefield of Point Pleasant, the chief event of Lord Dunmore's War, and reared largely among the descendants of the men who participated in that struggle." Lewis' great-grandfather, Benjamin Lewis, fought in the Battle of Point Pleasant and received wounds during his active participation in that pivotal engagement. One might imagine the vivid conversations Lewis had with those proud men -- only a generation or two removed from our nation's "Founding Fathers" -- who passed down the stories of their accomplishments on the field of battle to their own sons and daughters.

It stands to reason, therefore, that Virgil Lewis took enormous pride in his ancestor's role in the Battle of Point Pleasant. As a historian, however, he carefully avoided platitudes. In his book, Lewis took great pains to note that the battle, while important, did not signal the beginning of the Revolutionary War, and he scoffed at earlier writers' efforts to canonize the victors as the first Patriots of the American Revolution.

"Much error has been incorporated into the later writings regarding Dunmore’s War," Lewis wrote. "This is the result of a carelessness on the part of those, who without making research and investigation necessary to arrive at truth, seized rumors, traditions, and vague recollections, as sufficient authority upon which to base an assertion, and who substituted their own inferences for authenticated facts. These errors of statement have sometimes been repeated by considerate writers whose distrust was not excited; and this has increased the difficulties of pains-taking historians." Calling such errors "the gossip of history," Lewis hoped that his book would dispel the "myths, legends and traditions" associated with the Battle of Point Pleasant. Folklore and fairytale, however, persisted.

LORD DUNMORE'S WAR

Waged beneath the shadows of the British flag, and under the command of Virginia's Royal Governor, John Murray, the Earl of Dunmore, the Battle of Point Pleasant -- known as the Battle of Kanawha in some older accounts -- was the only major action of Lord Dunmore's War. In 1774, Lord Dunmore called upon Virginia's House of Burgesses to finance and support an army raised to quell violence on the frontier. Colonial settlers in territory south of the Ohio River sought to defend themselves against attack from Native Americans, who themselves sought to protect their hunting grounds from the white settlers "pressing down from the Alleghenies." Both sides claimed that the other had violated negotiated treaties protecting their right to occupy and hunt on the land. Bloodshed ensued.

|

| JOHN MURRAY, FOURTH EARL OF DUNMORE (ca. 1730–1809) Image credit: Library of Virginia |

Following a series of gruesome attacks upon the settlers by Indians, the Virginia legislature issued a plea to Lord Dunmore to respond:

"It gives me great pain, my Lord, to find that the Indians have made fresh encroachments and disturbances on our Frontiers; we have only to request that your Excellency will be pleased to exert those powers with which you are fully vested by the Act of Assembly, for making provision against Invasions and Insurrections, which we have no doubt, will be found sufficient to repel the hostile and perfidious attempts of those savage and barbarous Enemies."

With the support of the Virginia House of Burgesses, Lord Dunmore created two armies, personally leading seventeen hundred men from the north, while Colonel Andrew Lewis directed another eight hundred troops through the Kanawha Valley. A confederation of Indian tribes, led by the Shawnee Chief Cornstalk, gathered to meet Colonel Lewis and his men at the point of attack. On October 10, 1774, the Battle of Point Pleasant commenced.

After a long and brutal fight lasting for several hours and ultimately won in bloody hand-to-hand combat, Cornstalk's warriors were forced into retreat. The Virginians had held their ground, and in the process captured 40 guns, many tomahawks and supplies, and killed an indeterminate number of Indians. Lord Dunmore later forced Cornstalk to sign a peace treaty ceding to Virginia the Shawnee claims to all lands south of the Ohio River, thus opening the land to further settlement.

JOHN SEVIER'S PARTICIPATION IN THE BATTLE

Although no "official" roster of soldiers participating in the battle has ever been compiled, Lewis endeavored to list all those who fought at Point Pleasant in his book, relying upon information reported in Revolutionary War pension applications, as well as the personal stories and anecdotes told by descendants of the soldiers who fought in the battle.

Many of the battle's participants were blood relatives. According to Lewis, John Sevier fought at the Battle of Point Pleasant alongside his younger brother, Valentine, who was among the first to actively engage the enemy on the morning of the battle. Evan Shelby and his sons, Isaac and James, also drew arms together in this conflict, and Lieutenant Isaac Shelby's flanking maneuver ultimately turned the tide of the battle. This stealthy military tactic did not go unnoticed by the young John Sevier, who frequently used a similar movement against the Cherokees in subsequent engagements.

THE LEGACY OF THE BATTLE

In the years following the battle, veterans of the Battle of Point Pleasant and their descendants sought to commemorate their service, and drew tenuous connections to the American Revolution in their efforts. In 1899, Point Pleasant newspaper editor and publisher Livia Nye Simpson Poffenbarger organized an ambitious crusade in the State Gazette newspaper to have Point Pleasant officially designated the "first battle of the American Revolution," despite most historical interpretations which pointed to the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, on April 19, 1775. She boldly asserted that Lord Dunmore colluded with the Shawnee tribe, and never intended to join his northern forces with those of Colonel Lewis to the south. He had, according to Poffenbarger, anticipated the coming Revolutionary War and at Point Pleasant actually sought to weaken the citizen militia in advance of that conflict.

Lewis saw it as his mission to correct this historical narrative. In the preface of his book, Lewis challenged these efforts of commemoration, describing their reliance on the "vague recollections" of the descendants of the battle as "careless" and without authority. He supported his own scholarship by gathering his research from "original sources, documents and writings which were contemporaneous with the occurrence of the events described." Indeed, Lewis's work is filled with extracts from journals, memoirs, affidavits, letters, speeches, and documentary histories, giving his book a gravitas other more embellished histories sorely lacked.

|

| Portrait of Virgil A. Lewis, author of History of the Battle of Point Pleasant and West Virginia's first State Archivist Image credit: The West Virginia Encyclopedia |

Lewis later wrote a speech scolding this form of "manufactured history." He asserted:

"Every student of American history who has made research for truth in the sources of information, at this time readily available, is aware of the falsity of this statement, that Point Pleasant is the scene of the first battle of the Revolution. He regrets the perversion of historic truth in connection with it. When that battle was fought there was no revolution in progress; there were no United Colonies, or United States. Dunmore's War was waged between Virginians and Indians, no other Colony participating. The Indians were not allies of England then, nor did they become such until the Spring of 1778-four years after the battle-and no student of either Virginian or American Annals now questions the integrity of Lord Dunmore, or his faithfulness to the interest of the Colony of which he was the Executive head. There was not an English soldier with the Indians at Point Pleasant; nor did England, or a representative of the British Government, furnish a gun, an ounce of powder, nor a pound of lead, to them. The Virginians in that battle, were at that time, loyal to their Colonial Government, and had every confidence in their Governor. Colonel Charles Lewis was killed while wearing the uniform of an English Colonel; and other officers who fell on that field were wearing that of their rank."

CONCLUSION

There are certainly more recent works of scholarship about Lord Dunmore's War that one would do well to consult. Early indications are that Glenn Williams' recent release, Dunmore's War: The Last Conflict of America's Colonial Era, promises to be a compelling read. Still, Virgil Lewis's 1909 book, History of the Battle of Point Pleasant, has stood the test of time. Although written from the perspective of an early twentieth century historian and writer, Lewis' work provides valuable historical context, copious documentary notations, and details about specific soldiers who fought in the battle that genealogists will find useful in their own research.

As for John Sevier's role in the Battle of Point Pleasant, one might conclude that a portion of Sevier's gallant reputation as a Patriot hero rests upon the myth that he fought in both the "first" and "last" battles of the Revolutionary War -- Point Pleasant and Lookout Mountain -- despite clear historical evidence contradicting claims that these battles were ever a part of that conflict. While he may have fought in these engagements, his participation certainly did not bookend the American Revolution.

After reading Virgil Lewis' book, I must say that I feel a certain empathy for his fight for historical accuracy. Correcting long-standing historical narratives and pointing out myths and false legends can be an exhausting, solitary exercise, particularly when entire family legacies rest upon folktales that contradict fact and reason. Future generations and present-day historians owe a debt of gratitude to Virgil Lewis for taking a stand against "manufactured history."

History of the Battle of Point Pleasant by Virgil A. Lewis, The Tribune Company, West Virginia, 1909, is available in most public or university libraries, and may be purchased through any number of used book stores or antiquarian book dealers.

SELECTED SOURCES:

- Virgil A. Lewis. History of the Battle of Point Pleasant Fought Between White Men and Indians at the Mouth of the Great Kanawha River. Charleston, WV: The Tribune Printing Company, 1909.

- Charles H. Faulkner, Massacre at Cavett's Station. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press (2013), pp. 15-16.

- "Manufactured History: Re-Fighting the Battle of Point Pleasant." West Virginia History. Volume 56 (1997), pp. 76-87.

Gordon Belt is an information professional, archives advocate, public historian, and author of The History Press book, John Sevier: Tennessee's First Hero, which examines the life of Tennessee's first governor, John Sevier, through the lens of history and memory. On The Posterity Project, Gordon offers reflections on archives, public history, and memory from his home state of Tennessee.